Perianal abscess and Fistulae in Ano

What is a perianal abscess/anal fistula:

There are a number of glands present in the anus that produce mucous and lubricate the stool during defecation. These glands can get blocked and cause an infection, a collection of pus called and abscess. Sometimes after drainage of the abscess a tunnel forms that starts in the anus and exist on the anal area (this is termed a fistula).

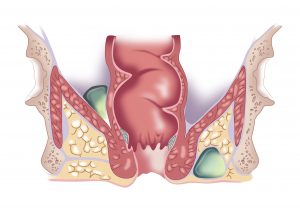

Cross-sectional image demonstrating sites of perianal infections. The relationship of the pus to the bowel, anal sphincter muscle and pelvic bones is important. Abscesses can communicate with the bowel and require surgical drainage.

Who is at risk:

The most common cause for the abscess and fistula is due to the “cryptoglandular theory”, which is where an abscess originates in a blocked anal gland and evolves into a fistula. There has been nothing identified that may predispose patient to “cryptoglandular fistulas”, though some can be recurrent. Other conditions that may precipitate anal fistulas and perianal infections are related to a history of:

- Crohn’s disease

- History of radiation (for treatment of cancers)

- Anal cancer

- Trauma (such as an injury during vaginal delivery)

- Sexually transmitted diseases

- Tuburculosis

What are the symptoms:

Pain in the anal area and discharge/staining on underwear with foul smelling pus.

Fevers, redness and sensation of a hot tender lump in the perianal area.

Pain with bowel movements.

Small volume anal bleeding.

How is an anal fistula diagnosed:

The constellation of symptoms provides the surgeon with a degree of suspicion related to the presence of the fistula. On visual inspection of the anal skin, and by performing an anal exam the surgeon can identify the area of inflammation and if a fistula is present, commonly a point of discharge can be seen on the external skin.

The internal opening (in the anal canal) is difficult to identify in the office. This usually requires a formal assessment in theatre under anaesthetic. Sometimes an MRI perineum or an endoanal (internal) ultrasound may be requested to help identify the fistula tract and its relationship with the anal sphincter (muscle that enables faecal continence).

What is the treatment of Anal fistula:

The acute management of perianal abscess and poorly draining fistulas is easy. Prompt and comprehensive drainage of all infective material is required. Sometimes a drain may be required to stay to facilitate long term drainage. Surgical intervention is the mainstay of treatment. Oral antibiotics may sometimes be required but are not routine taken long term.

Definitive repair of an anal fistula is complex. Treatment is based on the anatomy of the fistula: position of the internal and external openings, as well as the primary track and any associated “side branches” and the degree of sphincter involvement. Typically if there is persistence of discharge for greater than six weeks following repair, the repair has not been successful. Mr Bolshinsky is trained in a number of different techniques of fistula repair and will chose the procedure that is best suited to the individual patient.

Rectovaginal fistulae

What is a rectovaginal fistula:

A rectovaginal fistula is an abnormal communication between the bowel (anus or rectum) and the vagina. Patients are often distressed by symptoms of gas, liquid or frank faecal discharge from the vagina. The fistulas can be divided as high (rectovaginal) or low (anovaginal).

Who is at risk:

Rectovaginal fistulas are a rare condition in the community. Fistulas can form due to spontaneous formation of an abscess (cryptoglandular theory, see Anal Fistulae), however can also be as a result of:

- Obstetric injury or other trauma

- Crohn’s disease

- History of radiation (for treatment of cancers)

- Anal cancer

- Sexually transmitted diseases

- Tuburculosis

What are the symptoms:

A rectovaginal fistula is a communication between the bowel (rectum) and vagina. As such, symptoms are related to bowel content (gas, liquid, stool) being discharged from the vagina.

How is rectovaginal fistula diagnosed:

These fistulas are broadly divided into “high” where the communication is from the bowel and top of vagina) and “low” where the communication is from the anal canal. Investigations are dependent on the fistula location, but typically involve; X-ray & CT imaging, colonoscopy and examination under anaesthesia. The aim of these investigations are to define the origin, pathway and target sites of each fistula.

What is the treatment of rectovaginal fistulas:

Treatment is always surgical. The intervention is dependent on the anatomy of the fistula pathway and the rate of success is variable. Surgery should be attempted by experienced colorectal surgeons as these fistulas can be very difficult to treat. Temporary faecal diversion (a stoma bag) may be required.

Anal fissure

A fissure in ano is a small tear in the skin of the anal canal. These fissures can be very painful (like a paper cut). They can also be associated with bright red bleeding.

Who is at risk:

An anal fissure can occur in anyone, at any age. It is commonly associated with anal trauma. The most common presentation of an anal fissure is in association of the passage of hard, dry stool (following a period of constipation and consequent straining). Common conditions include:

- Chronic constipation and straining

- Diarrhea (and therefore frequent friction of anal skin)

- Anal receptive intercourse and other mechanical trauma

Conditions not associated with trauma include:

- Inflammatory bowel disease, specifically perianal Crohn’s disease

- Medical conditions that may affect bowel function or immune response:

- Anal cancer

- Leukaemia/lymphoma (particularly during chemotherapy)

- Sexually transmitted infections (including; HIV, syphilis, gonorrhoea, chlamydia)

What are the symptoms:

Common symptoms include:

- Pain during and up to several hour following defecation “like passing razor blades”.

- Constipation

- Rectal bleeding, most frequently fresh blood on the stool (not mixed in), on the toilet bowel or on toilet paper.

- Burning and itch around the anal area

- A palpable skin tag at the anal opening

How is an anal fissure diagnosed:

Typically, this is diagnosed by eliciting classical symptoms when taking a thorough medical history. On examination an acute fissure can be seen by parting the buttocks. A digital examination is typically avoided due to severe pain. Any fissure which is not at midline (anterior or posterior) is considered atypical, and a prompt examination under anaesthesia is required to rule out more sinister pathology such as an anal cancer.

What is the treatment of Anal fissures:

The treatment is divided into prevention and healing. Prevention is focused on optimizing bowel function. Healing is encouraged by reducing the anal sphincter spasm and improving blood flow to the fissure. Medical therapy and optimization is trialled first and is successful in more than 70% of cases. In patients who do not heal the fissure surgical options are than considered.

Medical:

Prevention involves optimising bowel function to ensure that the patient has regular, formed bowel movements without frequent diarrhea or constipation. Dietary changes and hydration are essential. A fibre supplement (psyllium husk) is commonly recommended with the target goal being 25-35g per day. It must be noted that fibre supplements need to be introduced gradually (start at 5g per day for 1 week), as it may precipitate bloating and increased flatulence that discourages patients from persisting with treatment.

Healing involves relaxation of anal sphincter spasm and improving blood supply to the fissure.

- Warm saltwater (SITS) baths are helpful for 5-10 minutes several times per day. Do not soak for too long as the skin can get macerated.

- Nitro-glycerine or Calcium channel blocker paste applied twice daily to the anal area helps to heal fissures in 70% of patients (improvements seen in 4-6weeks).

- Small doses of benzodiazepine may reduce anal spasm.

Surgical:

- Injecting Botulinum Toxin type A (BOTOX) into the anal sphincter temporarily paralyses the sphincter, therefore reducing anal spasm and improving the blood supply to the fissure. This is a well-recognized technique which has a good success rate and low complication profile.

- A limited (lateral) sphincterotomy is a day procedure performed under a general anaesthetic with a >95% success rate. This involves cutting a small amount of sphincter, and therefore reducing the anal spasm. This procedure is not reversable and therefore, particularly in women (who have smaller sphincters than men) it is performed with caution.

Haemorrhoids

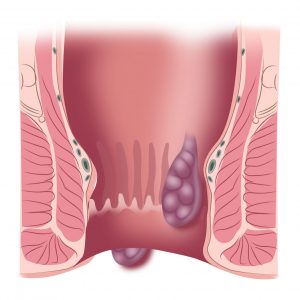

Haemorrhoids are a normal part of the human anatomy. Haemorrhoids assist the anal sphincter mechanism to maintain faecal continence. There are both internal haemorrhoids, that are located inside the anal canal, and external haemorrhoids, located at the anal opening. People are not aware of their haemorrhoids unless they cause symptoms.

Cross-sectional image of the anal canal, demonstrating two different sites where haemorrhoids can occur (internal and external).

Who is at risk:

Patients that may experience symptoms related to hemorrhoidal problems include:

- Low fibre diet, constipation and straining

- Diarrhea and increased frequency of bowel movement

- Prolonged sitting on toilet

- Pregnancy and vaginal deliveries

What are the symptoms:

Symptoms are related to size and position of the haemorrhoids. These include;

- Rectal bleeding (typically fresh blood on the stool, in toilet bowl or on toilet paper)

- Anal pain, particularly with bowel movement

- Anal itching and mucous discharge

- Protrusion of internal haemorrhoids that can return into the anal by self, or with digital pressure

How are haemorrhoids diagnosed:

Haemorrhoids are very common. It is essential to confirm that there is nothing more sinister that may be hiding amongst the haemorrhoids. At a minimum all patients with symptomatic haemorrhoids require a minimum of:

- Digital rectal exam

- Visual inspection of the rectum and anal canal

What is the treatment of symptomatic haemorrhoids:

A number of different surgical options are available for the treatment of haemorrhoids. These depend on the symptoms and size. As an adjunct to surgical options optimization of bowel function is recommended:

- Maintain soft, regular bowel movements, aiming to have 25-35g of fibre per day.

- Evaluate bowel habits and ensure that prolonged straining or sitting is avoided. Do not use the toilet to read or use electronic devices.

- Take a warm saltwater (SITS) bath to relieve discomfort following defecation.

Surgical techniques for treatment of haemorrhoids include:

- Rubber band ligation: A band is placed on the haemorrhoid pedicle to compress its blood supply. The haemorrhoid falls off within 7-12days and is often associated with a self-limiting bleed. This procedure is painless in most patients. There is a very small, but significant risk of the infection in the anal area.

- Doppler-guided haemorrhoidal artery ligation (HAL-RAR): This is a painless procedure where the haemorrhoidal vessels are sutured under doppler guidance. This technique addresses bleeding but is only limited in the improvement of skin tags.

- Excisional haemorrhoidectomy: This is a surgical procedure which involves cutting out the internal haemorrhoidal pedicle and the external anal tags. This is notoriously a very painful procedure, with the pain being most severe in the first seven days post resection.

- Evacuation of perianal haematoma: An external haemorrhoid can sometimes be isolated, without an internal haemorrhoidal pedicle. If this haematoma is seen within the first 48-72hours an incision and evacuation of the haematoma can be performed. Delayed presentation with perianal haematomas are treated with reassurance, as the haematoma gets re-absorbed and transforms into a skin tag over time.