Anatomy

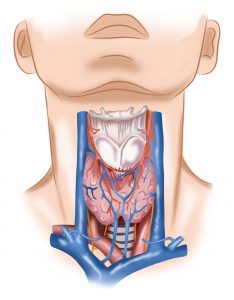

The thyroid gland is a butterfly shaped organ which is located in the front of your lower neck and is attached to the trachea (your airway). The thyroid is composed of thyroid follicles, which produce thyroid hormone, C cells, which produce calcitonin and supportive parafollicular cells. Adjacent to the thyroid are four parathyroid glands (two pairs, upper and lower glands). An important nerve (recurrent laryngeal nerve) which controls movement of your vocal cords is located behind the gland. Another nerve (external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve) which controls the tension in your vocal cords, for pitch or voice projection, is related to the superior pole of the thyroid gland. All of these structures are important to consider when performing thyroid surgery.

The thyroid and parathyroid glands are completely separate endocrine organs. The thyroid gland produces thyroid hormones (T3 triiodothyronine and T4 thyroxine) which have many functions in your body. Some of these include:

- Metabolism

- Thermoregulation

- Neurodevelopment

- Regulation of cardiac output

- Regulation of other bodily systems eg. sleep, sexual function and thought patterns

By contrast, the parathyroid glands are responsible for calcium metabolism.

The thyroid gland is a highly vascular gland, which is located just below the Adam’s apple, in the neck.

Thyroid Development

The thyroid begins to develop during the 3rd and 4th week of embryological life. It begins as a small outpouching in the base of the primitive tongue. It then descends to the base of the neck, where it is positioned in adult life. During its migration, the thyroid remains connected to the tongue via a thyroglossal duct. Normally, this degenerates by the end of week 5, but it can persist leading to developmental abnormalities.

The thyroid gland is affected by multiple disorders including:

- Auto-immune conditions eg Graves’, Hashimoto’s

- Structural abnormalities eg. solitary nodule, colloid goitre, multinodular goitre

- Developmental abnormalities eg. thyroglossal fistula, Lingual thyroid

- Functional disorders eg. solitary toxic nodule, toxic multinodular goitre

- Cancer

- Medications eg. amiodarone, contrast for certain radiology scans, interferon, lithium

Developmental abnormalities

Thyroglossal Duct Cysts and Fistula

A thyroglossal duct cyst is a fluid filled midline cyst that forms from a thyroglossal duct which fails to degenerate after thyroid migration. Because it is connected with the tongue, via the tract of thyroid descent, it will move during swallowing and protrusion of the tongue. A fistula is present if the cyst ruptures and communicates with the skin surface. Both can become infected. In very rare cases, thyroglossal duct carcinoma may develop. The treatment is surgery via a Sistrunk procedure.

Lingual Thyroid

Lingual thyroid is an abnormal mass of ectopic thyroid tissue seen in base of tongue caused due to embryological aberrancy in development of thyroid gland. The cause is unknown. Most of the ectopic tissue is seen in the tongue. Identification and proper management are essential, since they may be the only functioning thyroid tissue occurring in the body. Euthyroid patients and asymptomatic patients are followed-up regularly without any treatment. Surgery is indicated following failure of medical treatment, obstructive symptoms and other complications related to growth (bleeding, ulceration, cystic degeneration, malignancy).

Autoimmune thyroid diseases

Graves’ disease

Graves’ disease is the most common form of hyperthyroidism in Australia. It affects 3% of women and is substantially less common in men. Often it starts between the ages of 40-60 years but can occur at any age. Signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism include irritability, muscle weakness, sleeping problems, a fast heartbeat, poor tolerance of heat, diarrhea and unintentional weight loss. Other signs may include thickening of the shins (pretibial myxoedema), hair loss and eye bulging (exophthalmos). The exact cause is unclear; however, it is believed to involve a combination of genetic and environmental factors. A person is more likely to be affected if they have a family member with the disease. The onset of disease may be triggered by stress, infection or giving birth and patients with a history of other autoimmune diseases are more likely to be affected. The disorder results from an antibody, called thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI), that has a similar effect to thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH). These TSI antibodies cause the thyroid gland to produce excess thyroid hormones. The diagnosis may be suspected based on symptoms and confirmed with blood tests and a nuclear medicine scan. Typically, blood tests show raised thyroid hormones and TSI antibodies, low TSH, increased radioiodine uptake in all areas of the thyroid. There are three treatment options for Graves’: are radioiodine therapy, medications and thyroid surgery. Radioiodine therapy involves taking iodine-131 by mouth, which is then concentrated in the thyroid and destroys it over weeks to months. This causes hypothyroidism which is then with synthetic thyroid hormones. Antithyroid medications can also be given but have side effects and are not always successful. Surgery, to remove the entire thyroid, is a definitive treatment.

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, also known as chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis and Hashimoto’s disease. It affects about 5% of the population and is more common in women than men. In Hashimoto’s disease the thyroid gland is gradually destroyed by the body. Early on there may be no symptoms but gradually the thyroid may enlarge (goitre) and fail to function normally (hypothyroid). The cause is thought to be due to a combination of genetic and environmental factors. Diagnosis is confirmed with blood tests for TSH, T4, and anti-thyroid autoantibodies. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is typically treated with thyroid hormone replacement. Surgery is rarely required.

Structural thyroid diseases

Colloid goitre

A goitre is an enlargement of the thyroid. A colloid goitre is a diffuse and even enlargement of the thyroid. It may be asymptomatic, present as a mass in the neck or signs of underactivity (hypothyroidism). The most common cause of a colloid goitre is iodine deficiency. In Australia, our salt is iodized so this is less common. Other causes are certain medications, congenital problems and goitrogenic foods (excessive soy or brassica vegetables). Excluding functional or structural problems, a colloid goitre does not require surgery.

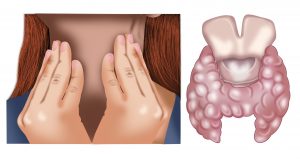

A goitre is an enlarged thyroid. It may be smooth (a colloid goitre) or nodular (a multi nodular goitre).

Multinodular goitre

Some thyroid glands become dramatically enlarged due to the growth of numerous nodules. These are called multinodular goitres. This condition is often hereditary or related to iodine deficiency. Surgery is indicated if the goitre is unsightly or causing pressure symptoms.

A multinodular goitre develops after repeated episodes of thyroid growth (hypertrophy) and regression (atrophy). Patients may be asymptomatic or have compressive symptoms such as shortness of breath, difficulty swallowing or a palpable lump.

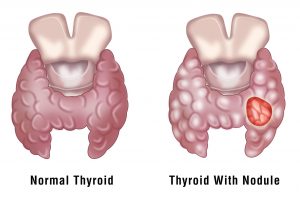

Thyroid nodules

Thyroid nodules are very common and are more common as we get older. Thyroid nodules can be symptomatic by causing an unsightly mass, difficulty swallowing or shortness of breath (pressure symptoms) or rarely pain. Most worrisome symptoms associated with a thyroid nodule might be new onset of a hoarse voice, rapid growth or craggy and hard to touch. As the use of imaging increases in medical practice, many thyroid nodules are detected incidentally during investigation of an unrelated issue. If a patient presents with a thyroid nodule, it is necessary to determine whether the nodule is functional (producing too much thyroid hormone resulting in hyperthyroidism) and the risk of cancer. The majority of thyroid nodules are benign; however, some are cancerous. Ultrasound and fine needle aspiration (FNA) are particularly useful and in many instances. This can be performed during your consultation with Dr Edwina, with permission saving time, cost and inconvenience. Thyroid cancer has increased worldwide over the past 30 years. Fortunately, with good care, the outcome is extremely favourable.

The gold standard technique for assessment of a thyroid nodule is to perform an ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration (FNA). This is a simple, quick office procedure.

Functional thyroid disease

Thyroiditis

Thyroiditis is a general term that means inflammation of the thyroid gland, not thyroid infection. Thyroid infections are virtually unheard of. Thyroid inflammation can occur for many reasons. Types of thyroiditis include Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, silent/painless thyroiditis, post-partum thyroiditis, radiation-induced thyroiditis, drug-induced thyroiditis, acute/suppurative thyroiditis (bacterial) and subacute/De Quervain’s thyroiditis (viral).

There are three phases to thyroiditis:

- Thyrotoxic phase. Thyrotoxicosis means that the thyroid is inflamed and releases too many hormones.

- Hypothyroid phase. Following the excessive release of thyroid hormones for a few weeks or months, the thyroid will not have enough thyroid hormones to release. This leads to a lack of thyroid hormones or hypothyroidism.

- Euthyroid phase. During the third euthyroid phase, the thyroid hormone levels are normal. This phase may come temporarily after the thyrotoxic phase before going to the hypothyroid phase, or it may come at the end after the thyroid gland has recovered from the inflammation and is able to maintain a normal hormone level.

There may be no symptoms. When symptoms occur, they may vary depending on the stage of the inflammation.

- Hyperthyroid phase: Usually short lasting (1-3 months.) If cells are damaged quickly and there is a leak of excess thyroid hormone, you might show symptoms of hyperthyroidism, such as:

- Being worried

- Feeling irritable

- Trouble sleeping

- Fast heart rate

- Fatigue

- Unexplained weight loss

- Increased sweating and heat intolerance

- Anxiety and nervousness

- Increased appetite

- Tremors

- Hypothyroid phase (more common): Can be long-lasting and may become permanent. If cells are damaged and thyroid hormone levels fall, you might show symptoms of hypothyroidism, such as:

- Fatigue

- Unexpected weight gain

- Constipation

- Depression

- Dry skin

- Difficulty performing physical exercise

- Decreased mental ability to concentrate and focus

Tests for thyroiditis may include:

- Thyroid function tests measure the amounts of hormones (thyroid-stimulating hormone or TSH, T3, and T4) in the blood. TSH comes from the pituitary gland and stimulates the thyroid gland to produce T4 and T3. The thyroid gland produces the hormones T4 and T3 that exert the action of thyroid hormone in the body. T3 and T4 are called thyroid hormones.

- Thyroid antibody tests measure thyroid antibodies that include antithyroid (microsomal) antibodies (TPO) or thyroid receptor stimulating antibodies (TRAb).

- Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) indicates inflammation by measuring how fast red blood cells fall. The ESR is high in sub-acute thyroiditis.

- Ultrasound sonogram of the thyroid, is used very frequently to evaluate the anatomy of the thyroid gland. It can show a nodule in the thyroid gland, a change in blood flow (Doppler mode) and echo texture (intensity/density) of the gland.

- Radioactive iodine uptake (RAIU) measures how much radioactive iodine is absorbed by the thyroid gland. The amount is always low in the thyrotoxic phase of thyroiditis.

Treatment is focused on the underlying cause as well as regulating thyroid function.

Solitary toxic nodule

At times a thyroid nodule may be functional, that is producing excess thyroid hormones in relation to the rest of the gland. This is called a toxic nodule or a ‘hot adenoma’. Diagnosis is made by confirmation of hyperthyroidism (blood tests) and then determining the cause for this (nuclear medicine scan). It is difficult to treat a toxic thyroid nodule with medication and so surgery is often indicated. If the rest of the thyroid is normal, only half (the half with the toxic nodule) needs to be removed.

Toxic multinodular goitre

This occurs when the thyroid is subjected to repeated rounds of stimulation (causing nodules) and removal of the stimulus (causing involution of nodules). The final pathology is a thyroid that is distorted by multiple nodules or variable size. When several of these nodules function excessively, the diagnosis is a toxic multinodular goitre. Typically, the treatment for this is surgery and the entire thyroid is removed.

Thyroid cancer

Over the past two decades the incidence of thyroid cancer has increased dramatically worldwide. Research has shown that this is not simply because of increased detection. Thyroid cancer of all stages of detection has become more common. Reasons are not understood.

Thyroid cancer most commonly affects peri or post-menopausal women but can occur at any age. Patients may have no symptoms or present with a lump or rarely a change in voice. Risk factors for thyroid cancer are previous radiotherapy to the head and neck and a family history of thyroid cancer.

Types of Thyroid Cancer

a) Papillary thyroid cancer (PTC)

This is the most common type of thyroid cancer, representing 75-85% of cases. It arises from the thyroid follicular cells and is most common in women, aged 20-50 years. PTC is often well-differentiated, slow-growing and localized to the thyroid gland. Metastases tend to occur via the lymphatics first. On microscopy PTC has characteristic ‘papillae’, hence its namesake. Papillary microcarcinoma is a subset of PTC which is defined as <1cm. Surgery remains the mainstay of treatment for PTC.

b) Follicular thyroid cancer (FTC)

This is the second most common type of thyroid cancer, representing about 15% of cases and also arises from thyroid follicular cells. Often older women are affected most frequently. It is impossible to differentiate between a follicular adenoma and a follicular carcinoma on fine needle aspiration and therefore diagnostic surgery is necessary. Hurtle cell thyroid cancer is considered a subset of FTC.

c) Medullary thyroid cancer (MTC)

These are rare cancers that arise from the parafollicular cells (C cells) of the thyroid, unlike either PTC or FTC. Approximately 25% of MTCs are genetic in nature, caused by a mutation in the RET proto-oncogene. When MTC occurs as part of a syndrome with parathyroid and adrenal tumours it is called multiple endocrine neoplasia. The treatment if MTC is surgery, a total thyroidectomy with a removal of the lymph nodes in the central neck. There is no role for adjuvant radio-iodine treatment.

d) Anaplastic thyroid cancer

This is a rare but extremely aggressive type of thyroid cancer. Curative treatment is unfortunately uncommon and therefore surgery does not play an active role in care. Palliative treatment consists of a combination of radiation therapy and chemotherapy.

The diagnosis and treatment of thyroid cancer follows a clear algorithm. Once a thyroid nodule is detected (either via clinical examination or imaging), in most cases it is recommended to perform a fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy. Ultrasound guided biopsy has a higher chance of being successful. Dr Edwina follows the recommendations set out by the American Association of Endocrine Surgeons (AAES). All thyroid nodules larger than 1cm or with suspicious features should be biopsied.

Bethesda Classification

This was established as a standardized, category-based reporting system for thyroid FNAs, and most recently updated in 2017. There are six diagnostic categories: 1) non-diagnostic, 2) benign, 3) atypia of unknown significance, 4) Follicular neoplasm, 5) suspicious for malignancy, 6) malignant. Each category has an implied risk of cancer, which are linked to evidence-based clinical management recommendations. This may be repeat FNA, clinical and ultrasound follow-up, molecular testing, removing half the thyroid (lobectomy) or removing all of the thyroid (total thyroidectomy).

Molecular Testing

While thyroid FNA is the diagnostic test of choice for thyroid nodules, to distinguish benign from malignant, it fails to classify in 15-30% of cases. Molecular testing has evolved, to help improve the accuracy of thyroid cytology for indeterminate cases. There are two types of molecular tests, ‘rule in’ (with a high positive predictive value eg. Afirma Gene Expression Classifier) and ‘rule-out’ (with a high negative predictive value eg Thyroseq Next Generation Sequencing). Molecular testing helps to guide the extent of surgery in cases where the risk of cancer is unclear. In the future they hold great promise guiding the role of radio-iodine therapy and potentially systemic therapy too. Presently, they are not readily available in Australia.

Radio-iodine Therapy (RAI)

Radio-iodine treatment is a type of internal radiotherapy, which specifically targets thyroid cells. Iodine 131 (I-131), is given via an injection (intravenously) and circulates throughout your body in your bloodstream and is uptaken by thyroid cells which have an affinity for iodine. The radiation in the iodine then kills the cancer cells. It is used for follicular and papillary thyroid cancer. There is no role for RAI treatment for medullary thyroid cancer as this arises from a different thyroid cell type that is not iodine avid. There are three scenarios when RAI might be recommended; to mop up microscopic cells left behind after surgery in cancers with a high risk of recurrence (remnant ablation), to treat thyroid cancer that has spread (adjuvant) or to treat thyroid cancer that is come back after it was first treated (treatment of known cancer). Before any type of RAI treatment, you will need to prepare. This will involve adjusting your medications and keeping a low iodine diet. Depending on the dose, you may need a period of isolation after therapy. Dr Edwina will explain this in more detail to you if necessary.

Risk of Recurrence after Surgery for Thyroid Cancer

The risk of recurrence of thyroid cancer after surgery, is based on distinct clinical and pathological factors. These include extension of cancer outside the thyroid gland, presence of spread to other organs, >3cm deposit within lymph nodes, incomplete surgery, certain subtypes of cancer and spread into blood vessels or lymphatics. Dr Edwina will explain this in more detail with you.

Thyroid Cancer Follow-Up

After surgery for thyroid cancer, typically you will be reviewed within 2 weeks, thereafter at six months and then annually. During cancer surveillance, you will have a neck examination and focussed ultrasound of the central and lateral neck (where thyroid cancer could spread to). We will also monitor your blood tests, thyroid function and thyroglobulin. If you have medullary thyroid cancer, we will also check your calcitonin levels.

Familial Endocrinopathies

Familial endocrinopathy describes a disorder in the function of an endocrine gland, which affects more members of the same family than can be accounted for by chance. The spectrum of familial tumour endocrinopathies is broad and complicated. In contrast to other tumour types, endocrine tumours can produce hormones, which may aid in diagnosis or pose unique and complex challenges. There are three groups to consider;

- Core Endocrine Tumour Syndromes eg. MEN1, MEN2

- Genetic Syndromes (main manifestations affect endocrine organs) eg. VHL, Cowden Syndrome

- Genetic Tumour Predisposition Syndromes (characterized by other clinical features but have a significant lifetime risk for rarer endocrine disorders) eg. FAP

The major endocrine tumours and associated syndromes are outlined in the table below.

Specialist management is very important to ensure appropriate surveillance and tailored treatment, including early genetic testing and family cascade screening of at-risk family members. Dr Edwina will discuss this with at length, if necessary.

Thyroid FAQ’s

- What is hyperthyroidism?

Hyperthyroidism is the condition that occurs due to excessive production of thyroid hormone by the thyroid gland. Thyrotoxicosis is the condition that occurs due to excessive thyroid hormone of any cause and therefore includes hyperthyroidism. Hyperthyroidism may be caused by Graves’ disease, a toxic thyroid nodular a toxic multinodular goitre. The symptoms of hyperthyroidism are:

- Anxiety and other mood changes

- Racing heart and palpitations

- Weight loss and increased appetite

- Light or no periods

- Diarrhea

- Increased sweating

- Insomnia

- What is hypothyroidism?

This refers to when the thyroid does not function normally. It may be caused by a congenital problem, autoimmune disorders, iodine deficiency or manifest post-surgery (after thyroidectomy called iatrogenic hypothyroidism). The symptoms of hypothyroidism are the reverse of for hyperthyroidism and include;

- Depression

- Muscle weakness

- Weight gain and reduced appetite

- Heavy periods

- Constipation

- Cold intolerance

- Fatigue

- What type of anaesthesia will I have for thyroid surgery?

You will have a general anaesthesia. You will be completely asleep during the operation and will not feel or remember anything.

- How much of my thyroid will be removed?

That depends on your condition. When the entire thyroid is removed, the operation is called a total thyroidectomy and you will need thyroid hormone medication for life (usually one tablet a day). A thyroid lobectomy or hemi thyroidectomy is when half of the thyroid is removed. Sometimes after hemithyroidectomy, patients still require thyroid medication although the dose is less. Dr Edwina Moore will discuss with your which operation is best for your condition and why.

- How is thyroid surgery performed?

You are first put to sleep with a general anaesthetic. Dr Edwina Moore is very mindful of cosmesis, so will endeavour to hide the incision within a natural neck skin crease on your neck and to keep it as small as possible. During the operation, Dr Edwina Moore uses modern energy devices to divide and seal blood vessels, a technique which is commonly referred to as ‘suture-less thyroidectomy’. She meticulously identifies and dissects both important nerves related to the thyroid and preserves the normal parathyroid glands. In re-operative cases she also engages a nerve monitoring device, to confirm functionality during a difficult dissection.

- What is a high-volume surgeon?

Dr Edwina Moore is an experienced, well trained and high-volume thyroid surgeon. Her upmost priority is to perform a technically excellent operation. High volume is a termed used in surgical literature to indicate the level of experience a surgeon has with a particular operation. It directly relates to the number of these procedures performed. Evidence shows that high volume surgeons consistently have better patient outcomes. This is best practice endocrine surgery.

- Will I need lifelong medication?

After thyroid surgery, almost all patients are commenced on thyroid hormone replacement medication, typically on the first post-operative day. The initial dose is determined by your weight and subsequently titrated to blood tests of your thyroid function. Thyroid hormones are necessary to maintain normal metabolism. Many patients unfortunately worry about weight gain associated with thyroid medication. This is not true if dosed correctly.

- What are the potential risks of thyroid surgery?

All surgery involves risk, although we do our best to minimize this. It is important to weigh these against the risks of not having surgery. The risk of a serious complication in a healthy person is very rare. Potential risks specific to thyroid surgery are:

- Permanent voice damage

- Permanent parathyroid damage

- Bleeding after surgery (needing another operation)

- Wound fluid collection (seroma)

- Wound infection

- Keloid or hypertrophic scar

- How long will I be hospitalised?

Most patients are admitted to the hospital on the morning of their surgery and are able to go home the next day. At times, if there has been an extensive lymph node dissection or medication needs to be adjusted, this may be one or two nights more. Generally, when you can eat, drink, pass urine and gas, walk around the ward and your pain is controlled you are ‘fit’ for home.

- Will I have stitches?

You will have some internal stitches in the muscle that your body will absorb naturally. Your skin will be expertly closed with medical glue and a medical band-aid (called a ‘steri-strip’). There will be no skin stitches that need removal. This technique ensures an optimal cosmetic outcome, but it is important that you avoid any activity where you will unnecessarily strain.

- Will I have a scar?

Yes. All incisions once healed will leave a scar. The aim is to perform a safe and complete operation, with the best cosmetic outcome (smallest, most discrete scar). Scars continue to remodel (and change in appearance) over 12months, up to 3 years. All patients heal (and therefore scar) differently. It is important to keep the wound clean, free from tension and covered from the sun. A thyroid scar is a horizontal scar on the neck. Dr Edwina will aim to place your scar is a natural skin crease so that it is barely visible.

- When will I know the findings of the surgery?

Dr Edwina Moore will discuss the operation with you at multiple stages whilst you are in hospital. The final pathology report which requires meticulous study of the surgical specimen usually takes one week and therefore will be available at the time of your post-operative review.

- Will I have any physical restrictions after my surgery?

In general, your activity level depends on the amount of discomfort you experience. Most patients return to work in a week or two, and you are able to drive as soon as your head can be turned comfortably without discomfort. For the best wound healing it is advisable not to perform any heavy activity (eg. Lifting >7kg) for 4 weeks after surgery. It is also not advisable to bathe or swim with a fresh wound.

- What is the long-term follow up after thyroid surgery?

This depends on the reason that you had surgery and Dr Edwina Moore will explain this to you in person during your consultation. As a minimum if you have had thyroid surgery, you will need lifelong monitoring of your medication and thyroid function (although this doesn’t have to be too onerous). For patients with thyroid cancer, you will be seen every six months initially and then annually thereafter.